|

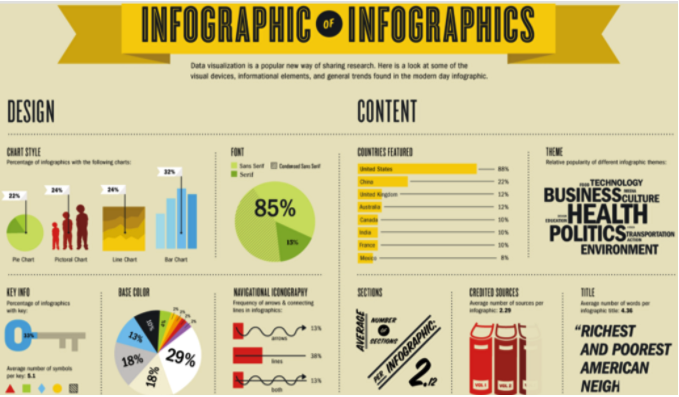

Undraa Maamuujav, Jenell Krishnan, & Penelope Collins Infographics are visual representations designed to present information, data, and knowledge quickly and clearly (Krauss, 2012). A writing curriculum that explicitly teaches writers how to develop infographics as an authentic method of planning their ideas and communicating them to an intended audience may hold unique affordances for their writing development. By engaging students in developing infographics as a part of the writing process, teachers create an opportunity for students to compose within a legitimate, multimodal genre used in many public and private sectors. Moreover, teaching students how to create infographics before they compose their full-text drafts places greater emphasis on effective communication and reinforces the value of planning—a behavior demonstrated among successful writers (Graham & Harris, 1994).

By Jacob Steiss Interested in guest blogging for the National WRITE Center? See our guidelines by clicking here.

By Frank Guttler, Guest Blogger

Why do we tell stories? This is an interesting question to offer at the beginning of a blog on digital storytelling. Storytelling is a way for people to make sense of their worlds. It’s a natural part of humanity, re-living scenes from the past, replaying episodes from time gone by. One method of contemporary storytelling is digital storytelling—a process leading to the production of short films that unite a script with different multimedia elements, such as images, video, music, and narration –often an author’s own voice (G. A. Hull & Nelson, 2005). Advocates for its use believe that it enhances the learning of five 21st century skills helpful in worlds beyond the classroom (Robin, 2008) and traditional academic literacy skills (Vu, Warschauer, Yim, 2019). In the technology-enhanced classroom, digital storytelling is a unique, engaging, student-centered, creative process during which students practice their writing and language skills. Students also develop visual and digital literacy, while refining their understanding of key content. Visual language can be understood as a system that communicates through visual elements. It is perceived by our eyes and interpreted by our brain, which receives the signal and transforms into sensations, emotions, actions, and thoughts. Screen language can evoke emotions that may be on the page of a script and the performance of the actor, enhanced by the use of composed camera angles to create a near universally comprehended visual language. A language with it’s unique vocabulary and grammar across mediums. So, with all the prior knowledge and experience gained from watching TV and movies, why do most videos shot on our digital devices look like amature home movies? To address this, teachers might ask themselves, how can I leverage my students’ prior experiences with TV, film and other visual media to support their development of digital stories? How might I develop learning opportunities that scaffold students’ comprehension of complex visual language so they “write” rich, engaging and personal stories that achieve their own purposes as writers? Although we quickly learn to read the visual language around us, “writing” visually—by accessing screen vocabulary and grammar to communicate rather than just comprehend—is a skill some think reserved for highly trained media professionals. This is simply untrue. Teachers interested in integrating digital storytelling in the classroom may begin by

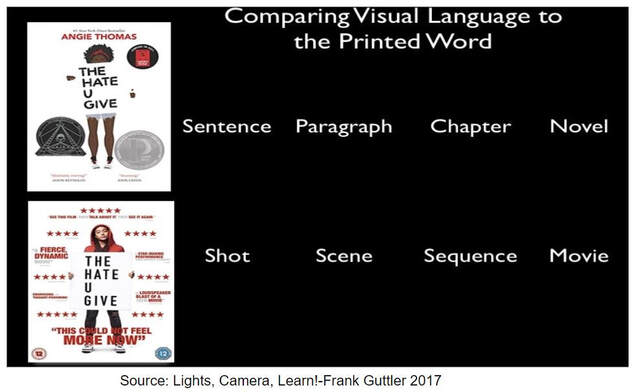

Learning to consume, evaluate, understand and especially create media for the screen may improve students' classroom engagement, academic performance, and their interpersonal skills. To build on these affordances, teachers need foundational learning experiences (and access to needed technology) to use filmmaking/digital storytelling/visual language, whatever you call it, as a means of engaging students in the mastery of more traditional notions of literacy. However, New forms of literacy are viewed as multiple, multimodal, and multifaceted making the creation of new media, to some, as important a skill as writing a sentence. It’s a matter of literacy. Or rather, literacies. Understanding Visual Grammar using the context of Written Grammar Imagine the wild and uncontrolled look of a home movie. Do all those long continuous shots; wild moves and dizzying zooms make for compelling viewing? This is an example of the average person’s ‘default mode’ of event documentation instead of storytelling. Those who are familiar with a written language’s structure and syntax might also find similarities of that shooting style with the classic run-on sentence; subjects & actions, nouns & verbs all blurring together on screen. The effect is, well, challenging to read and understand.

What is the difference between a shot and a scene? These are terms from the film and television world that are often used interchangeably by many when trying to talk critically about film and video. The key to understanding the difference is also the key to understanding the grammatical difference between a sentence and a paragraph.

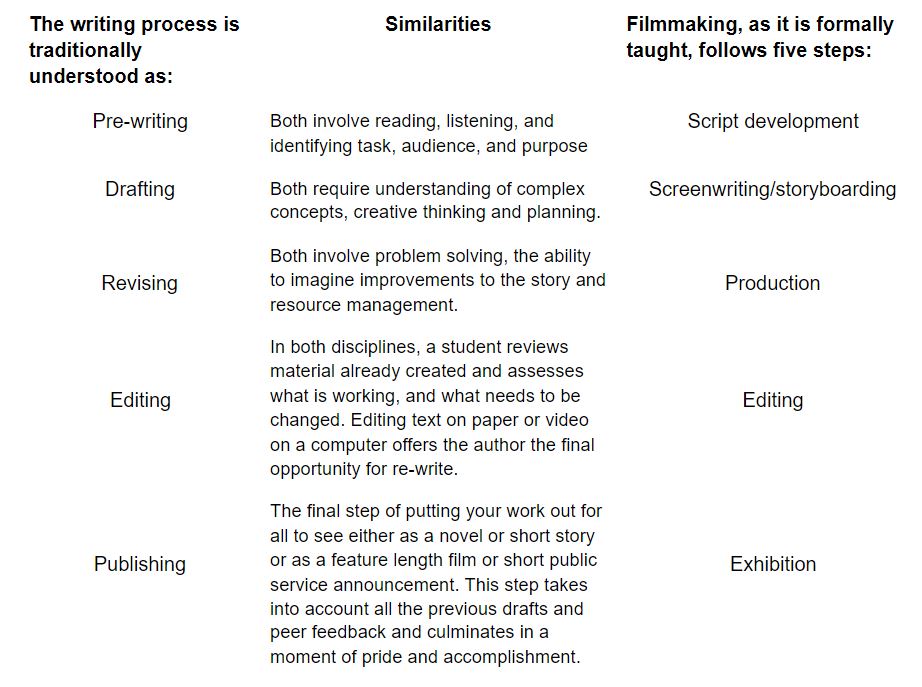

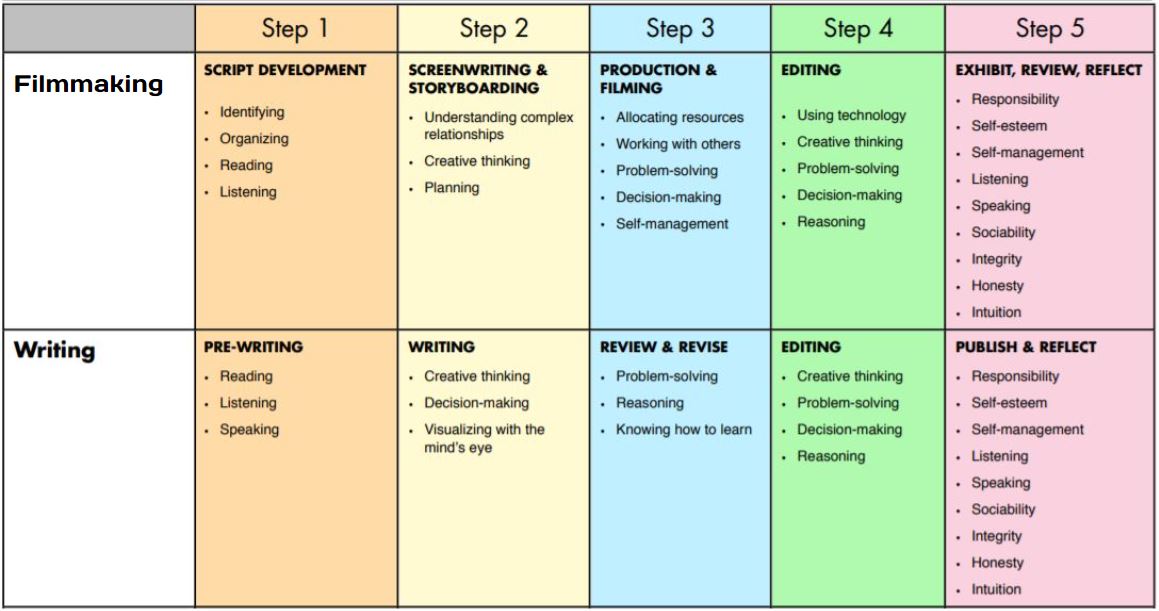

If a shot can be compared to a visual sentence then a scene can be further understood as a visual paragraph. The Writing Process & The Filmmaking Process Aligned Comparing the basic element of a visual medium like film like a shot to a basic linguistic construct like a sentence is a good start to deconstructing and decoding visual language in the context of more readily understood frameworks, like the Writing Process. When compared to the writing process, filmmaking lends itself to the idea that conceptualizing, preparing, producing and presenting a film or video can be understood in familiar terms to the average educator.

For many teachers, making this conceptual connection has become a first step to demystifying the filmmaking process and as result, allowed for more students to demonstrate what they know using the modern medium of digital video as part of core learning pedagogy. Source: American Film Institute Screen Education Handbook, 2007 The Writing Process comes alive for Digital Storytelling students in UC Irvine’s 2020 Summer Virtual Writing Project. The Show Must Go On! Staging the 36th year of the UCI Youth Summer Writing Project (SYWP) as a series of virtual events meant that I needed to build an online digital storytelling course for the program from the ground-up, a challenging experience for me— an educator and storyteller. The alignment of the filmmaking process and the writing process was a perfect fit for the Writing Project’s ethos. It was clear to me that there has never been a better time to engage students’ with their words, voices and images. Students of the 2020 SYWP would also be engaging with their own identity and their family heritage.

This four week, 24-hour online course challenged students to write personal narratives about themselves and then research a mini-documentary tracing their family’s history all while building a foundation of basic video skills like camera composition, editing, and sound production. Most of the students were using personal or school issued mobile devices like iPads or smartphones while some worked on laptops and chromebooks. iMovie and WeVideo were the most used video editing tools. All students completed their projects using only mobile devices.

To avoid the time-consuming trap of front-loading all the technical skills like shooting, sound or editing, I adopted a ‘just-in-time’ teaching approach to introducing new skills as the requirements of the project progressed. For instance, I taught students how to record the sound of a script reading as their projects became ready for a voice-over. Production breakout sessions of 45-60 mins followed, either individually or in small groups to work on new production skills, writing challenges or give peer-to-peer feedback. Students stayed logged into the Zoom session and worked independently in breakout rooms, requesting help or feedback from the instructor as needed. At around the 30-minute mark, we engaged in a mid-session group check-in for a show & tell of new skills or progress on projects. This was followed by another independent work period. Then, we concluded the session with a final re-group and debrief on the work of the day and a preview which included our learning pursuits for the next session.

The Writing Project seeks to foster strong writing fundamentals as a foundation for lifelong writers, and my short mini-lessons and main projects aligned with such a mission. To build on that foundation, I also sought to enhance students’ learning with contemporary digital and technical skills. Taken together, my students’ agency inspired them to write stories and make videos as part of how they express themselves to the world. The thing I don’t have to hope is that their new awareness of how to ‘read’ & ‘write’ with video, has developed broad literacy skills and awareness I believe they need for today’s increasingly connected, digital world. I leave you with the same question we began with. Why do we tell stories? For teachers, how might such a question reveal your students’ identities and build meaningful connections among your community of learners, even at a distance?

Interested in guest blogging for the National WRITE Center? See our guidelines by clicking here.

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

WRITE Center: Writing Research to Improve Teaching and EvaluationThe research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305C190007 to University of California, Irvine. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

|

© COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|